Describe the characteristics of sensory receptors.

1. Modality-Specific

Each receptor is sensitive to a specific type of stimulus (called a modality), such as light, sound, pressure, or temperature.

Example: Photoreceptors respond to light; mechanoreceptors respond to pressure or touch.

2. Location

Receptors can be:

- Exteroceptors – detect external stimuli (e.g., in skin, eyes).

- Interoceptors – detect internal body conditions (e.g., blood pressure, pH).

- Proprioceptors – detect body position and movement (e.g., in muscles, tendons).

3. Threshold

Receptors require a minimum intensity of stimulus (called the threshold) to activate and produce a response.

4. Transduction

Receptors convert the stimulus (e.g., heat, light) into an electrical signal (action potential or graded potential).

5. Adaptation

Some receptors adapt over time:

- Phasic receptors – adapt quickly (e.g., you stop noticing a strong smell after a while).

- Tonic receptors – adapt slowly or not at all (e.g., pain receptors).

6. Intensity Coding

The strength of a stimulus is encoded by:

- Frequency of action potentials (stronger stimulus = more frequent impulses).

- Number of receptors activated (stronger stimulus = more receptors stimulated).

7. Receptive Field

- Each receptor has a specific area where it detects stimuli.

- Smaller receptive fields = greater sensitivity (e.g., fingertips).

- Larger fields = less precise detection (e.g., back).

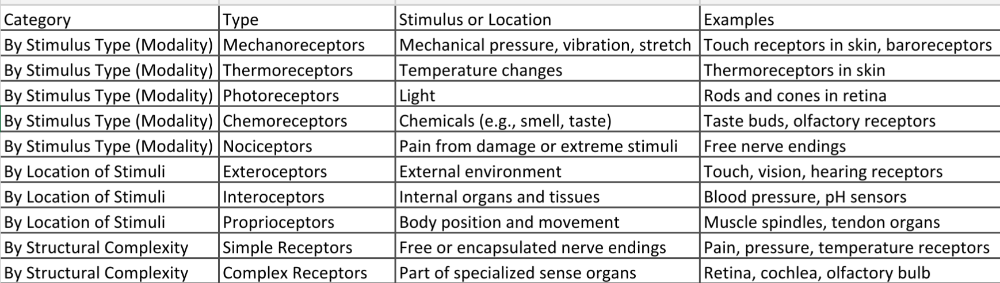

How are sensory receptors categorized?

Describe the nature of the receptor (generator) potential.

A receptor (or generator) potential is a graded electrical response produced in a sensory receptor when it detects a stimulus.

- It is not an action potential, but a local change in membrane potential.

- Caused by the opening of stimulus-gated ion channels (e.g., from pressure, heat, or light).

- The size (amplitude) of the receptor potential depends on the intensity of the stimulus.

- Stronger stimulus → larger receptor potential.

- If the receptor potential is strong enough to reach threshold at the first node of Ranvier (or trigger zone), it triggers an action potential that travels along the sensory neuron.

Describe the significance of receptor (generator) potential.

1. Initiates Sensory Signaling:

- It is the first step in converting a physical stimulus into a neural signal (transduction).

- Without it, the nervous system wouldn’t detect sensory input.

2. Determines Action Potential Firing:

- If the receptor potential reaches threshold, it leads to action potentials.

- The frequency of action potentials reflects stimulus strength.

3. Encodes Stimulus Intensity:

Stronger receptor potentials → more frequent action potentials → brain interprets as a stronger sensation (e.g., more intense pain or pressure).

4. Occurs in Both Specialized Receptors and Free Nerve Endings:

- In specialized receptor cells (e.g., photoreceptors), it may trigger neurotransmitter release.

- In sensory neurons with free nerve endings (e.g., pain receptors), the receptor potential directly leads to action potentials.

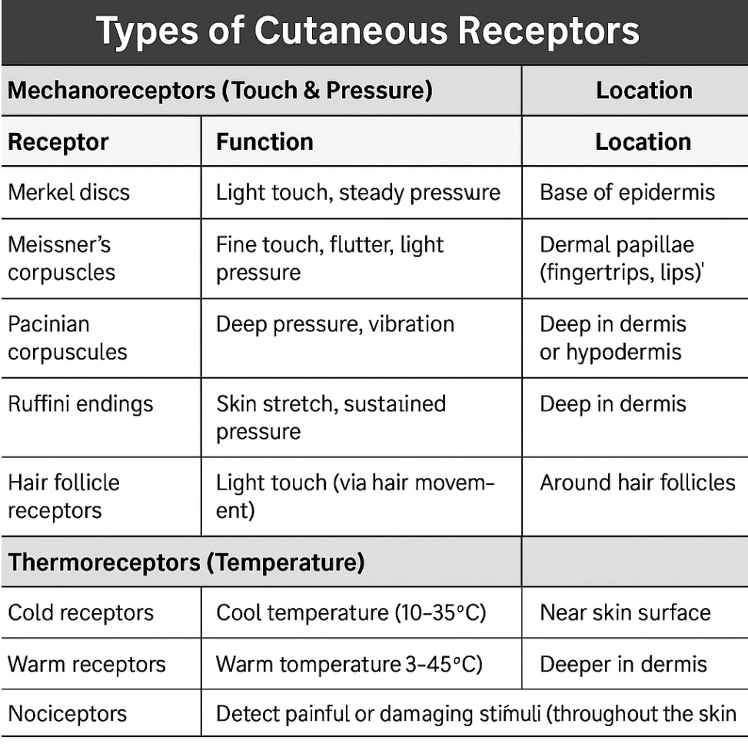

Describe the types of cutaneous receptors

Extreme temperatures activate nociceptors instead of thermoreceptors.

3. Nociceptors (Pain)

- These detect painful or damaging stimuli (chemical, thermal, or mechanical).

- Found throughout the skin.

- Use free nerve endings (no special structures).

- Trigger a protective response (e.g., pulling your hand away from something hot).

4. Proprioceptors (Less common in skin)

Mostly found in muscles and joints, but some may sense skin stretch to help detect body position.

Define sensory acuity and explain how it is affected by receptor density and lateral inhibition.

Sensory Acuity: It means how well you can feel small details — like how close two touches can be before they feel like one.

1. Receptor Density

- More touch receptors in an area = better feeling.

- Fingertips have lots of receptors → feel tiny details.

- Back has fewer → touch feels less sharp.

2. Lateral Inhibition

- When one receptor sends a strong signal, it blocks weaker nearby signals.

- This makes the main touch stand out more clearly.

- Helps your brain tell exactly where you're being touched.

Identify the modalities of taste and explain how they are produced.

1. Sweet

Stimulus: Sugars (e.g., glucose, sucrose), artificial sweeteners.

How it's produced: Sweet molecules bind to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on taste cells. This triggers a signaling cascade, leading to neurotransmitter release.

2. Salty

Stimulus: Sodium ions (Na⁺), mainly from table salt (NaCl).

How it's produced: Na⁺ ions enter directly through ion channels in the taste cell membrane. This causes depolarization, which triggers a signal to the brain.

3. Sour

Stimulus: Hydrogen ions (H⁺) from acidic substances (like lemon juice).

How it's produced: H⁺ ions enter the cell or block potassium channels, causing depolarization and a signal to the brain.

4. Bitter

Stimulus: Toxic or bitter compounds (e.g., caffeine, quinine).

How it's produced: Bitter compounds bind to GPCRs on taste cells. This starts a chemical cascade that alerts the brain — often as a warning signal.

5. Umami (Savory)

Stimulus: Glutamate (found in meats, cheeses, soy sauce).

How it's produced: Glutamate binds to specific GPCRs on taste cells. Triggers a signal that the food is protein-rich.

How the Brain Gets the Signal: The taste receptor cells activate sensory neurons, which carry signals to the brain via: Facial nerve (VII), Glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and Vagus nerve (X)

Explain how odorant molecules stimulate their receptors and describe how the information is conveyed to the brain.

1. Detection: Odorant Binds to Receptor

- Odorant molecules (chemicals in the air) enter the nasal cavity when you sniff or breathe.

- They dissolve in the mucus covering the olfactory epithelium (a special patch of tissue in the nose).

- The odorant binds to a specific receptor on an olfactory receptor cell (a kind of sensory neuron).

2. Receptor Activation (Signal Transduction)

Each olfactory receptor is a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR).

When an odorant binds:

- The GPCR activates a G-protein called Golf.

- This starts a chemical reaction inside the cell that leads to opening of ion channels.

- Na⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions enter → the neuron depolarizes → an action potential is triggered.

3. Signal Travels to the Brain

- The action potential travels along the axon of the olfactory receptor cell, which forms part of the olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I).

- The nerve fibers pass through tiny holes in the cribriform plate of the skull to reach the olfactory bulb (just above the nasal cavity).

4. Processing in the Brain

In the olfactory bulb, the signal goes to structures called glomeruli, where it is sorted.

From there, the signal travels to:

- The olfactory cortex (for conscious smell perception),

- The limbic system (for emotional and memory-related responses),

- And other brain areas like the amygdala and hypothalamus.

Describe the structures of the vestibular apparatus and explain how they function to produce a sense of equilibrium.

The vestibular apparatus is a part of the inner ear that helps maintain balance and spatial orientation (equilibrium). It detects head position and movement using fluid, hair cells, and gravity.

1. Semicircular Canals

- There are three canals: anterior, posterior, and lateral — each in a different plane (3D directions).

- They detect rotational (angular) movements of the head.

How they work:

- Each canal has a swollen area called the ampulla, which contains a crista ampullaris with hair cells covered by a jelly-like cupula.

- When you rotate your head, the fluid (endolymph) inside the canal lags behind due to inertia and pushes the cupula, bending the hair cells.

- This generates nerve impulses about head rotation.

2. Utricle and Saccule (part of the otolith organs)

- These detect linear acceleration and head position relative to gravity.

- Utricle: horizontal movements (e.g., moving forward in a car)

- Saccule: vertical movements (e.g., going up in an elevator)

How they work:

- Inside each is a structure called the macula, containing hair cells embedded in a gel with otoliths (tiny calcium carbonate crystals).

- When the head tilts or moves straight, gravity or acceleration causes the otoliths to shift, bending the hair cells.

- This bending sends signals about tilt or movement to the brain.

Explain how sound waves result in movements of the oval window and then the basilar membrane.

1. Sound Waves Enter the Ear

Sound waves enter through the external auditory canal and strike the tympanic membrane (eardrum), causing it to vibrate.

2. Vibration Passes Through the Ossicles

- Vibrations from the tympanic membrane are transferred to the ossicles (tiny middle ear bones): Malleus → Incus → Stapes

- The stapes presses against the oval window, a membrane that connects the middle ear to the inner ear.

3. Movement of the Oval Window

- The stapes pushes on the oval window, creating waves in the fluid (perilymph) inside the cochlea (part of the inner ear)

- This converts mechanical energy into fluid waves inside the cochlea.

4. Fluid Waves Move the Basilar Membrane

Fluid waves travel through the scala vestibuli and scala tympani (chambers in the cochlea).

This motion causes the basilar membrane (in the middle chamber) to vibrate at specific locations, depending on sound frequency:

- High-pitched sounds vibrate near the base (stiff, narrow part).

- Low-pitched sounds vibrate near the apex (wider, more flexible part).

5. Activation of Hair Cells

- The vibrating basilar membrane pushes hair cells (in the organ of Corti) against the tectorial membrane.

- This bends the stereocilia on the hair cells, opening ion channels and triggering nerve signals sent to the brain via the cochlear nerve.

Explain how movements of the basilar membrane at different sound frequencies (pitches) affect hair cells.

The Basilar Membrane Responds to Pitch (Frequency)

- The basilar membrane inside the cochlea vibrates at different spots depending on the pitch (frequency) of the sound:

- High-frequency (high-pitched) sounds → vibrate the base of the cochlea.

- Low-frequency (low-pitched) sounds → vibrate the apex (tip) of the cochlea.

Why This Happens:

- The basilar membrane is stiff and narrow at the base, and wide and flexible at the apex.

- High-pitch sounds need a stiff surface → activate hair cells at the base.

- Low-pitch sounds move more flexible areas → activate hair cells at the apex.

How This Affects Hair Cells:

Hair cells sit on the basilar membrane, topped with tiny projections called stereocilia.

When the membrane vibrates:

- The hair cells in that area move up and down.

- This bends the stereocilia against the tectorial membrane.

- Ion channels open, causing a nerve impulse.

- The specific location of activated hair cells tells the brain what pitch the sound is.

Describe how action potentials are produced, and their neural pathways.

How Action Potentials Are Made

An action potential is an electrical signal that a nerve cell (neuron) uses to send messages.

Steps:

1. Resting: Neuron is at rest: inside is more negative than outside.

2. Stimulus Happens: A signal (like touch or smell) causes sodium (Na⁺) channels to open. Na⁺ rushes in → inside gets less negative.

3. Threshold is Reached: If enough Na⁺ enters, the neuron hits –55 mV and fires.

4. Depolarization: More Na⁺ enters → inside becomes positive (~+30 mV).

5. Repolarization: Na⁺ channels close, potassium (K⁺) channels open. K⁺ flows out → inside goes back to negative.

6. Reset: The neuron returns to resting state, ready to fire again.

(Neural Pathway): How the signal travels through the body:

1. Sensory Neuron: Detects something (like heat, pressure) and Sends signal to the spinal cord or brain

2. Processing: The brain or spinal cord understands the signal.

3. Motor Neuron: Sends a signal out to muscles

or glands to respond.

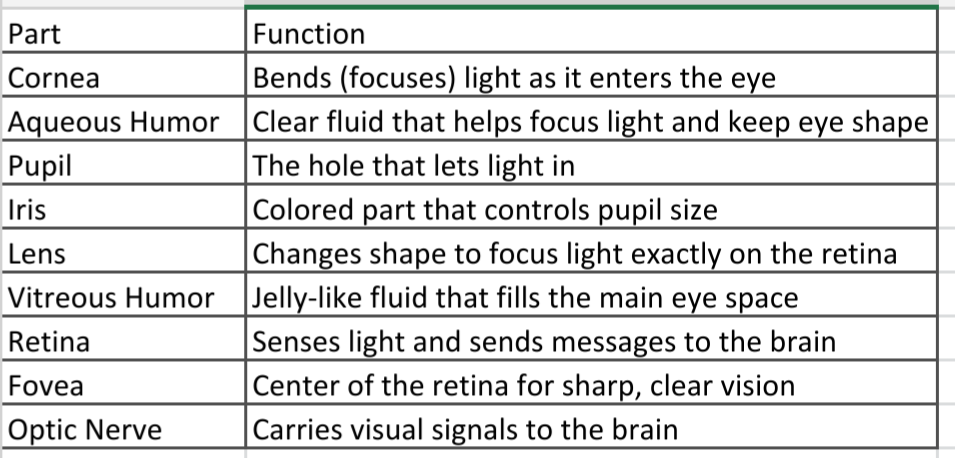

Describe the structures of the eye, and how these focus light onto the retina.

How Light is Focused:

1. Light enters the eye through the cornea, which bends the light.

2. The pupil lets in more or less light (controlled by the iris).

3. The lens fine-tunes the focus: Flattens to see far away, and Bulges to see up close

4. Light goes through the vitreous humor.

5. The light lands on the retina, where photoreceptors detect the image.

6. The optic nerve sends the picture to your brain.

Explain how accommodation at different distances is accomplished.

Accommodation is the process by which the eye changes the shape of the lens to focus on objects at different distances. This is done by the ciliary muscles, suspensory ligaments (zonules), and the lens.

How It Works:

For Near Objects: Ciliary muscles contract, Suspensory ligaments loosen, and Lens becomes rounder (thicker)

This increases the lens's curvature to bend light more, focusing the image on the retina.

For Distant Objects: Ciliary muscles relax, Suspensory ligaments tighten, and Lens flattens (thins)

This reduces the curvature of the lens, bending light less to focus distant images on the retina.

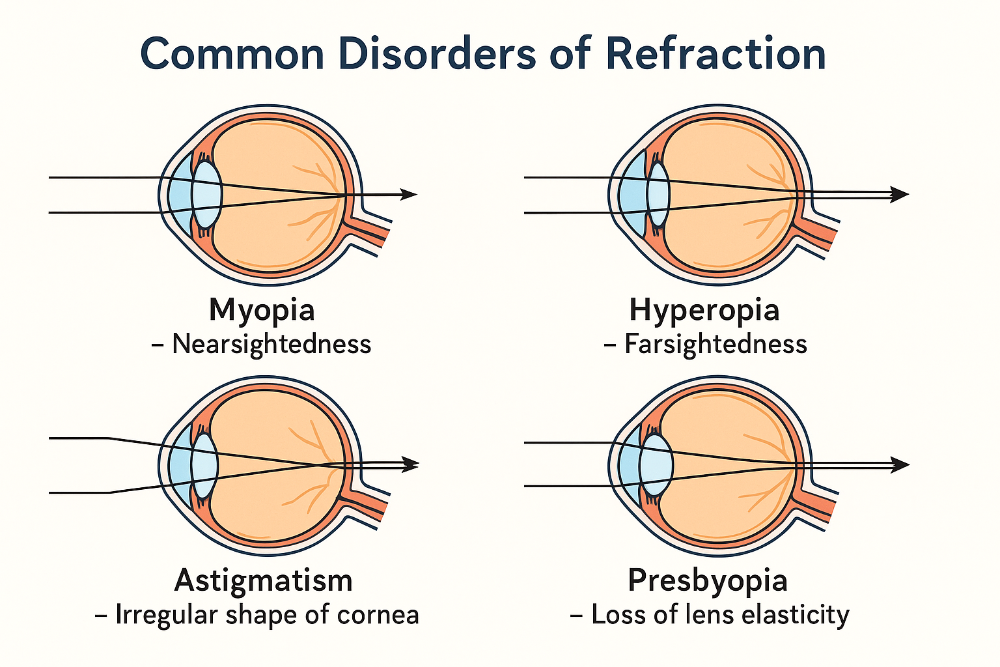

Explain common disorders of refraction

1. Myopia (Nearsightedness)

- Problem: Light focuses in front of the retina.

- Cause: Eyeball is too long or cornea too curved.

- Symptoms: Difficulty seeing far objects clearly.

- Correction: Concave lenses diverge light before it enters the eye.

2. Hyperopia (Farsightedness)

- Problem: Light focuses behind the retina.

- Cause: Eyeball is too short or cornea too flat.

- Symptoms: Difficulty seeing near objects clearly.

- Correction: Convex lenses converge light to focus it sooner.

3. Astigmatism

- Problem: Light focuses at multiple points due to an uneven cornea.

- Cause: Cornea or lens is irregularly shaped.

- Symptoms: Blurred or distorted vision at all distances.

- Correction: Cylindrical lenses compensate for uneven curvature.

4. Presbyopia

- Problem: Lens becomes less flexible with age.

- Cause: Aging of the lens and loss of elasticity.

- Symptoms: Difficulty focusing on close objects, especially reading.

- Correction: Reading glasses, bifocals, or progressive lenses.

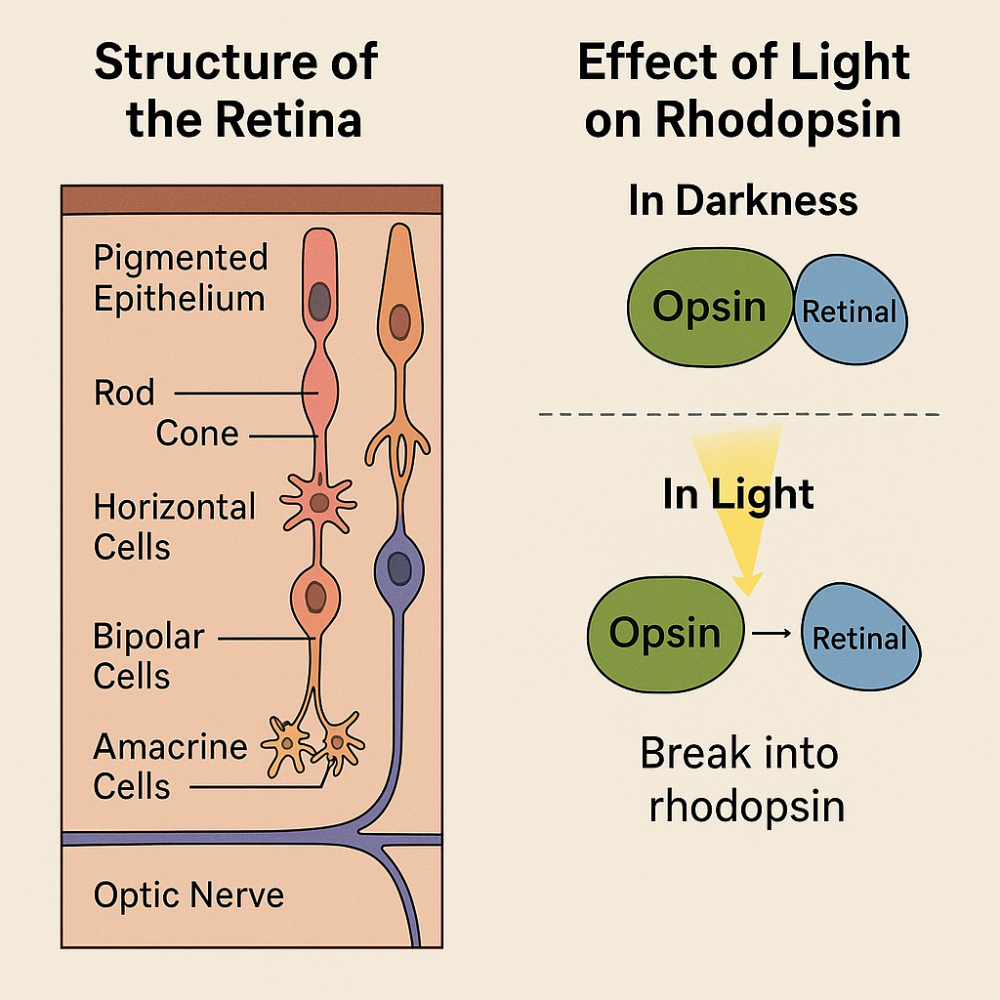

Describe the structure of the retina and how light affects rhodopsin

Rhodopsin and Light:

Rhodopsin is found in rod cells.

It consists of: Opsin (protein) and Retinal (light-sensitive molecule from vitamin A)

In Darkness: Rhodopsin is whole and active. Rods depolarize and release glutamate, which inhibits bipolar cells. No signal is sent to the brain (no vision signal).

In Light: Light causes rhodopsin to split → opsin + retinal. Rods hyperpolarize and stop releasing glutamate. This activates bipolar cells, which excite ganglion cells.

Signal is sent via optic nerve to the brain → visual perception.

Explain how light affects synaptic activity in the retina and describe the neural pathways of vision.

Light & Synaptic Activity in Retina:

In Darkness: Photoreceptors (rods) are active. They release glutamate. Glutamate blocks the signal → no vision signal

In Light: Light stops glutamate release. Bipolar cells are activated. Ganglion cells send signals to the brain

Neural Pathway of Vision (Simple Steps):

1. Light hits photoreceptors in the retina

2. Signal goes to bipolar cells

3. Then to ganglion cells

4. Ganglion cells form the optic nerve

5. Optic nerve goes to the optic chiasm (fibers cross)

6. Continues through the optic tract

7. Reaches the thalamus (lateral geniculate nucleus)

8. Ends in the primary visual cortex (in the brain’s occipital lobe)

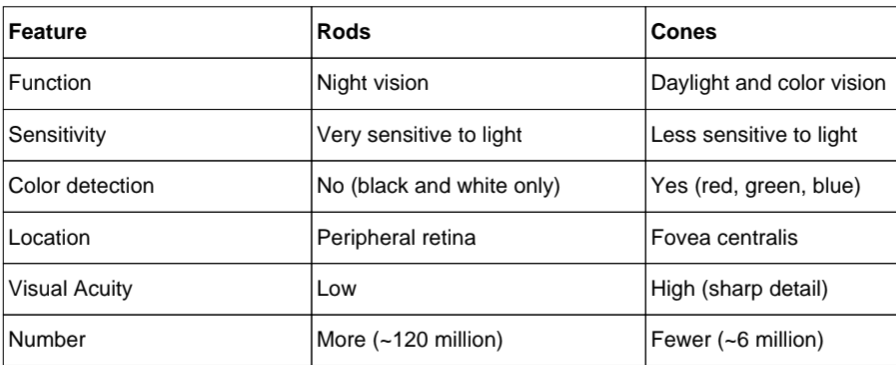

Compare the function of rods and cones and describe the significance of the fovea centralis.

Fovea Centralis (Importance):

- A small pit in the center of the retina

- Packed with cones only (no rods)

- Sharpest vision and best color discrimination

- Used for reading, recognizing faces, and fine detail