Define Pharmacodynamics

the branch of pharmacology concerned with the effects of drugs and the mechanism of their action

Define law of mass action

The rate of a chemical reaction is directly proportional to the concentrations of the reactants.

In Other Words:

- The more reactants you have, the faster the reaction will go (at least at the beginning).

- At equilibrium, the ratio of product and reactant concentrations is constant.

What is a dissociation constant?

The dissociation constant (Kd) measures how tightly a ligand (like a drug) binds to a target (like a receptor or enzyme).

Kd is the concentration of a ligand at which half of the target sites are occupied.

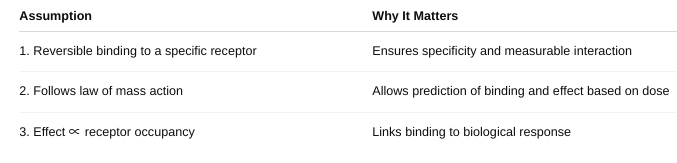

What are the three assumptions that must be made to have a ligand binding and physiological effect of a drug?

How does Affinity relate to the dissociation constant?

If a drug has a low Kd, it binds well — meaning it has high affinity for its target.

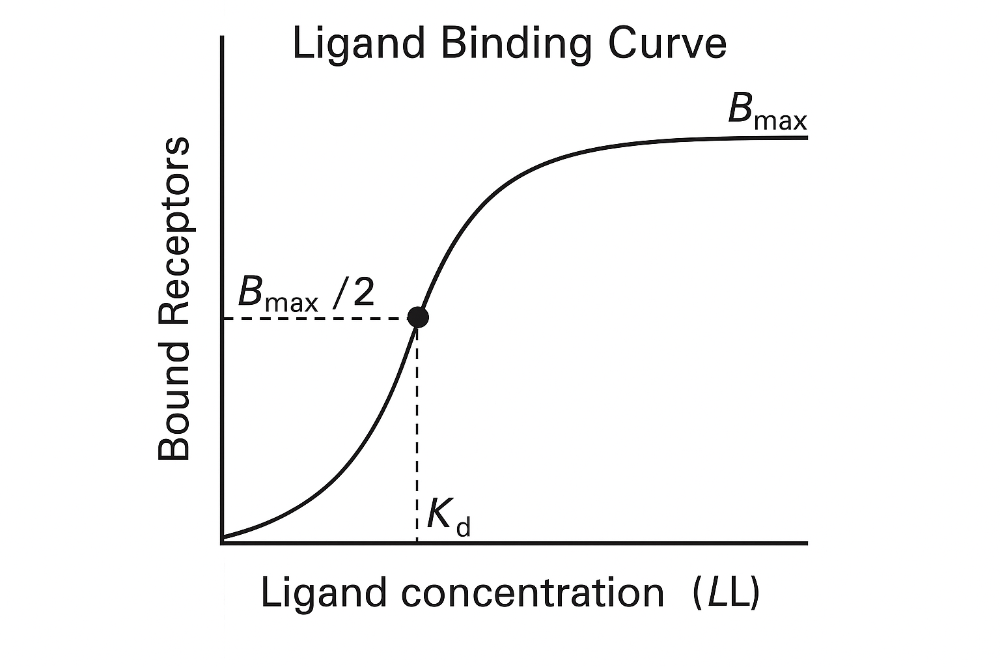

Draw a Ligand Binding Curve. Label axes and constants. Be able to explain. (figure 2-1)

Key point:

- The curve is **hyperbolic** (or **sigmoidal** on a

log scale).

- As ligand concentration increases, more receptors

get occupied — until it **levels off** at maximum binding.

1. **At low ligand concentrations**:

- Few receptors are

occupied.

- Binding increases sharply with small increases in [L].

2. **At Kd**:

- Half the receptors are bound.

- This

is a key point to compare different drug affinities.

3. **At high concentrations**:

- Most receptors are

saturated.

- Curve **plateaus** at **B max**.

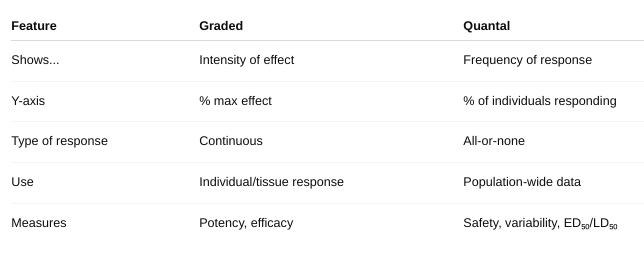

The Graded Dose Response Curve

Shows the magnitude of a response in a single individual (or a tissue/cell) as the dose increases.

- X-axis: Drug dose (log scale)

- Y-axis: Response (as a % of maximum effect)

Key Features:

Continuous curve – smooth increase in response with increasing dose. Measures intensity of effect.

- Used to calculate: EC₅₀: Dose that gives 50% of the maximal effect., Efficacy (max effect the drug can produce), and Potency (how much drug is needed to produce effect)

The Quantal Dose-Response Curve

Shows the percentage of a population that shows a defined response at each dose.

- X-axis: Drug dose (log scale)

- Y-axis: % of individuals responding

Key Features: All-or-none responses — either the effect occurs or doesn’t (e.g., sleep, death). Measures frequency of response across a population.

- Used to determine: ED₅₀: Dose that produces the desired effect in 50% of people, TD₅₀: Dose causing toxicity in 50%, LD₅₀: Lethal dose for 50% of subjects, and Therapeutic Index (TI) = TD₅₀ / ED₅₀

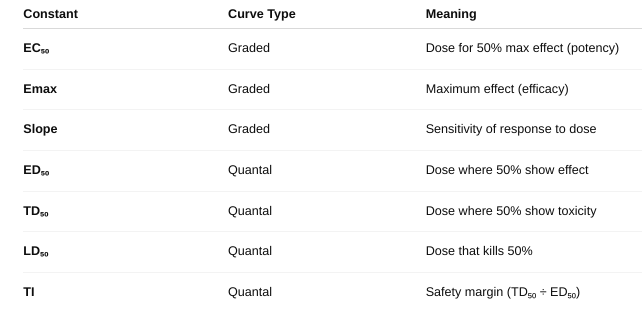

What are the differences? (figure 2-2, figure 2-3)

What are the constants you can gather from these curves?

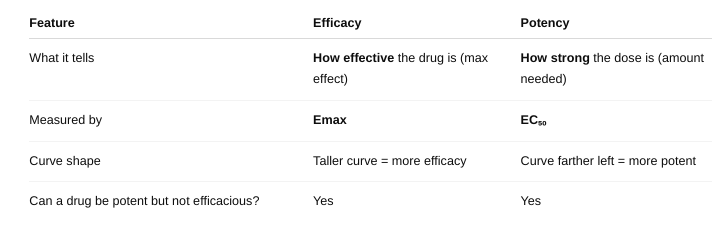

What is efficacy? potency?

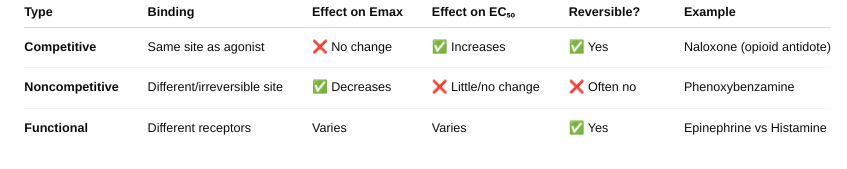

Identify/explain the types of Antagonists. give example. (figure 2-4, figure 2-6, figure 2-7)

What is a spare receptor? What is its effect on competitive and non-competitive antagonist? (figure 2-8, figure 2-9, table 2-1)

a receptor that does not need to be occupied for a drug to produce maximum effect.

Competitive Antagonist

With spare receptors, the system can tolerate receptor blockage and still achieve Emax — because not all receptors need to be occupied. So, competitive antagonists just shift the dose-response curve to the right (increase EC₅₀), but Emax is unchanged.

- You see increasing antagonist shifts the curve rightward but max response still achievable because of spare receptors.

Noncompetitive Antagonist

Normally, noncompetitive antagonists reduce Emax (since their block can’t be reversed). BUT — if there are spare receptors, the drug can still achieve Emax despite some receptors being blocked.

So: Low doses of noncompetitive antagonists may not affect Emax if spare receptors are present. Only at higher doses, when too many receptors are blocked, will Emax decrease.

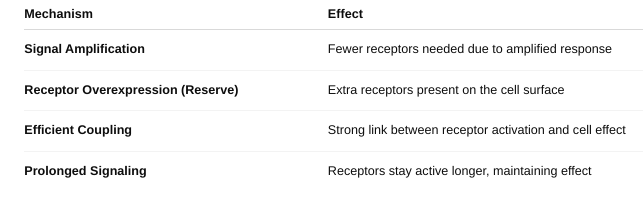

What are possible mechanisms for spare receptor effect?

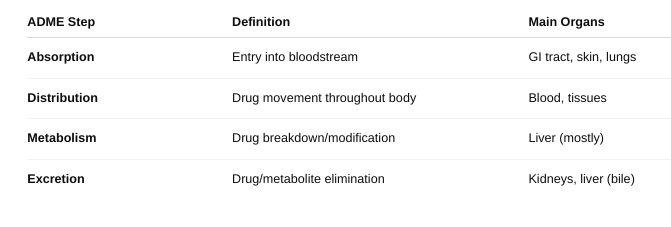

Define each principle of ADME.

What role do Biological Membranes play in ADME?

Absorption: Membranes determine whether a drug can enter the bloodstream.

Oral drugs must pass through intestinal epithelial membranes. Only lipophilic, non-ionized, and small molecules can easily diffuse. Others require carrier proteins or active transporters.

Distribution: Membranes control where the drug goes in the body.

Drugs must cross capillary membranes and cell membranes to enter tissues. The blood-brain barrier is a special tight membrane that protects the brain and restricts drug entry. Protein binding in plasma can also affect distribution across membranes.

Metabolism: Membranes regulate entry of drugs into metabolic organs and cells (especially liver cells).

Drugs must enter hepatocytes (liver cells) through membranes for enzyme processing. Membranes inside the liver cell compartmentalize enzymes (e.g., in the smooth ER for CYP450).

Excretion: Membranes are involved in drug removal, especially in kidneys and liver.

In the kidney, drugs cross membranes in nephrons (filtration and secretion). In the liver, drugs/metabolites can be secreted into bile via transporters. Transport proteins can pump drugs out of cells for elimination.

o Define FLUX.

the rate of movement of a drug (or any molecule) across a biological membrane.

o Define pH trapping

the process where a drug becomes ionized in a compartment with a different pH, causing it to get “trapped” and unable to cross membranes easily.

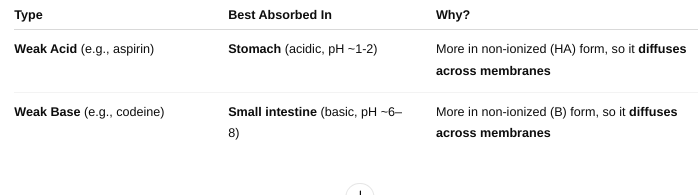

o Define weak acid and weak base?

o Where would a Weak Acid best absorb? Where would a Weak Base best Absorb?

A weak acid is a molecule that partially donates protons (H⁺) in solution.

A weak base is a molecule that partially accepts protons (H⁺) in solution.

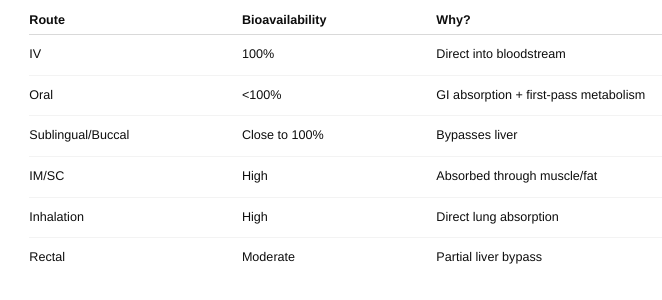

• Define bioavailability.

the fraction (or percentage) of an administered drug that reaches the systemic circulation in its active form.

• Does this change given the route of administration? Why or why not?

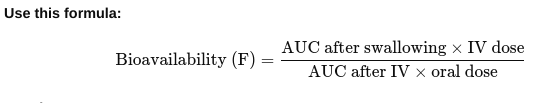

• How do you measure bioavailability?

Give the drug two ways:

Once directly into the vein (IV) — this is 100% bioavailable. Once by another way (like swallowing it).

- Take blood samples over time for both methods to see how much drug gets into the bloodstream.

- Draw a graph of drug level in blood vs. time for both methods.

- Calculate the area under each graph (AUC) — this shows the total drug that entered the blood.

Result: If F = 1 (or 100%), all the swallowed drug got into the blood. If less than 1, some drug was lost during absorption or metabolism.

• What is first pass metabolism

when a drug taken by mouth is partially broken down by the liver (and sometimes the gut wall) before it reaches the bloodstream.

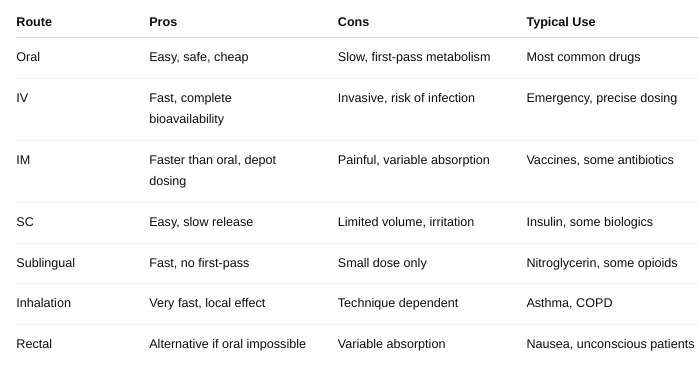

• What are the pros/cons of the different types of route of administration? (Table 3-1 and Table 3-2)

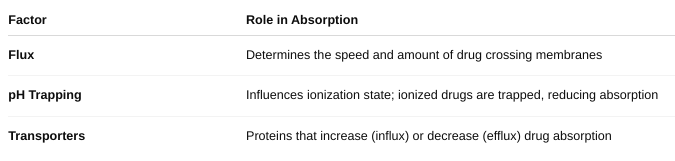

What role does FLUX play in absorption?

• What role does pH trapping play in absorption?

• What role do drug transporters play in absorption?

• Define APPARENT Volume of Distribution

a theoretical volume that relates the amount of drug in the body to the concentration of drug in the blood or plasma.

It tells you how extensively a drug distributes into body tissues compared to the blood.

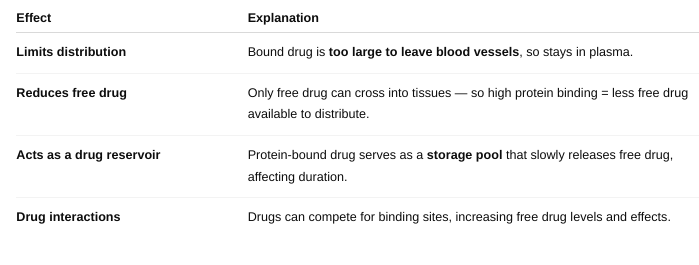

• What effect does plasma protein binding have on distribution?

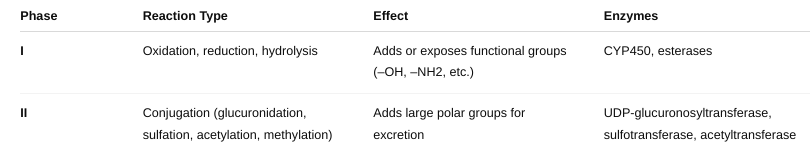

• What reactions are included in Phase I reactions?

• What reactions are included in Phase II reactions?

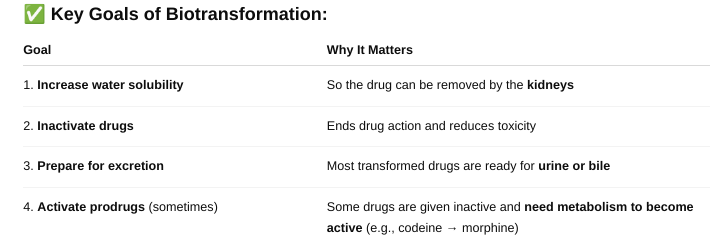

• What is the point of bio-transformations?

Biotransformation is the process by which the body chemically modifies drugs (and other foreign substances) to make them easier to eliminate

• Elimination Kinetics

describe how the body removes a drug over time — mainly through metabolism (liver) and excretion (kidneys).

o Define Half-life (t1/2)

the time it takes for the concentration of a drug in the blood to decrease by 50%.

If you have 100 mg of drug in your body and the half-life is 2 hours, then:

- After 2 hours → 50 mg left

- After 4 hours → 25 mg left

- After 6 hours → 12.5 mg left

- And so on…

How many half-lives does it typically take to eliminate a drug, typically?

It typically takes about 4 to 5 half-lives to eliminate a drug from the body.

By 4–5 half-lives, over 95% of the drug is gone, which is generally enough for it to be considered "eliminated" for clinical purposes.

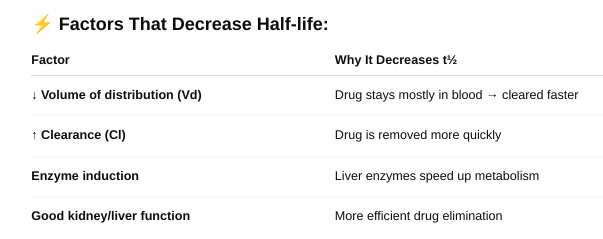

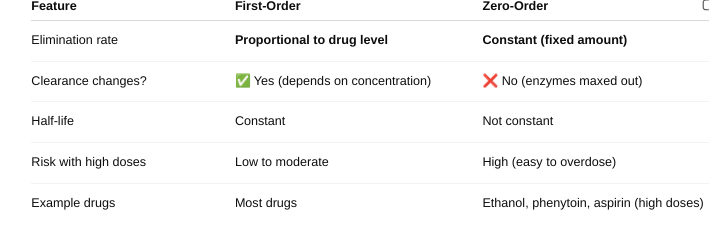

What types of factors affect half-life? (Table 3-5)

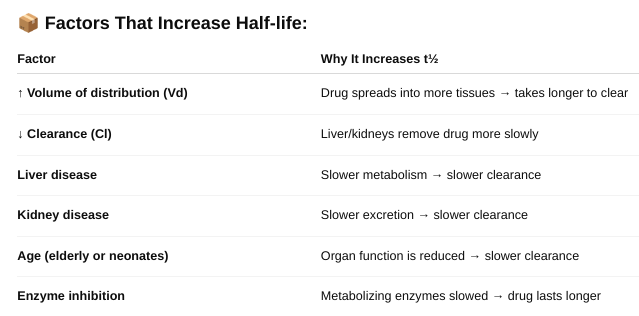

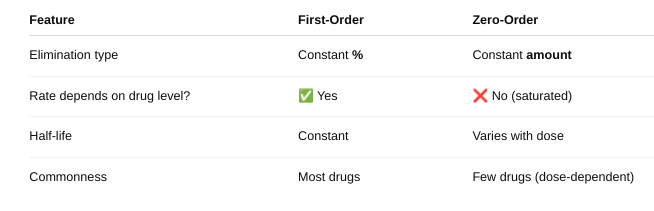

o Define zero and first order kinetics.

Explain the differences in the rate of elimination.

Explain the differences in the half-life.

First Order Kinetics: Half-life is constant — it stays the same no matter the drug dose.

- A fixed percentage of drug is eliminated in each half-life (e.g., 50%). You can predict how long the drug stays in the body. Used to calculate dosing intervals and time to steady state.

- Half-life = 2 hours

- 100 mg → 50 mg → 25 mg → 12.5 mg

- Each step = 2 hours

Zero-Order Kinetics: Half-life is NOT constant — it changes with the drug dose.

- The body eliminates a fixed amount (not a percentage) per hour. As dose increases, half-life gets longer because elimination is saturated. It’s hard to predict drug levels — higher risk of toxicity.

- 100 mg drug, eliminating 10 mg/hour:

- 100 → 90 (1 hr),

- 90 → 80 (1 hr),

- Time to reach 50 mg is not a fixed number of hours

When do saturation kinetics apply?

Saturation kinetics apply when...

✔ Drug concentration is high

✔ Metabolism or transport is saturated

✔ Body can't keep up with elimination

✔ Drug follows zero-order kinetics

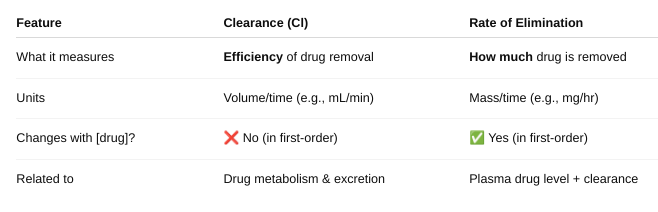

• Define Clearance and Rate of Elimination

• Figure 3-11. What do the toxic, therapeutic and sub-therapeutic ranges mean on these graphs?

o Why do you see “peaks and troughs” instead of a smooth line?

Therapeutic Range: The drug concentration range where the medication is effective without causing harm. Within this range, the drug produces the desired therapeutic effect. Staying within this range is the goal of dosing.

Toxic Range: Drug concentrations above the therapeutic range. At these levels, the drug may cause adverse or toxic effects. Avoiding concentrations in this range helps prevent side effects or overdose.

Sub-Therapeutic Range: Drug concentrations below the therapeutic range. The drug level is too low to produce the desired effect. Doses or frequency may need adjustment to reach therapeutic levels.

Why Do You See “Peaks and Troughs” Instead of a Smooth Line?

When a drug is given in doses at intervals (e.g., every 8 hours), drug levels rise after each dose (peak) and then fall as the drug is eliminated (trough).This causes a sawtooth pattern rather than a smooth curve.

- Peaks show the highest concentration after dosing.

- Troughs show the lowest concentration before the next dose.

- Maintaining peaks below toxic and troughs above sub-therapeutic levels is crucial for safe and effective therapy.

• What is the difference between a loading and maintenance dose?

Loading Dose

Purpose: Quickly raise the drug concentration in the blood to the therapeutic range.

When used: For drugs with long half-lives where reaching steady state with regular dosing would take too long.

How it works: A larger initial dose is given to “load” the body with drug rapidly.

Effect: Achieves desired drug levels quickly, before starting maintenance dosing.

Maintenance Dose

Purpose: Keep the drug concentration within the therapeutic range over time.

When used: After loading dose (or from the start if no loading dose needed).

How it works: Smaller doses given at regular intervals to replace the drug eliminated by the body.

Effect: Maintains steady-state drug concentration.

What are you taking into consideration when calculating dosages?

Patient Factors

Age: Children and elderly often need dose adjustments due to differences in metabolism and clearance.

Weight/Body Surface Area: Dosages often scale with body size, especially in pediatrics.

Organ function: Liver and kidney function affect drug metabolism and elimination.

Disease state: Conditions like heart failure or liver disease can change drug distribution and clearance.

Genetics: Some people metabolize drugs faster or slower (pharmacogenetics).

Pharmacokinetic Parameters

Clearance (Cl): Rate at which the drug is removed from the body.

Volume of Distribution (Vd): How extensively the drug distributes into tissues.

Half-life (t½): How long the drug stays in the body.

Bioavailability (F): Fraction of the dose that reaches systemic circulation (especially important for oral dosing).

Drug Factors

Therapeutic range: The drug concentration that is effective but not toxic.

Route of administration: Affects bioavailability and onset of action.

Formulation: Immediate vs. extended-release affects dosing frequency.

Dosing Goals

Loading dose: To quickly reach therapeutic levels.

Maintenance dose: To maintain steady-state levels.

Dose interval: How often to give the drug based on half-life.

Drug Interactions

Some drugs increase or decrease metabolism or clearance of other drugs.