Instructions for Side by Side Printing

- Print the notecards

- Fold each page in half along the solid vertical line

- Cut out the notecards by cutting along each horizontal dotted line

- Optional: Glue, tape or staple the ends of each notecard together

BMD 315 Module 3 Study Guide/Learning Objectives

front 1 Describe the features of the cellular environment (inside and outside). | back 1 Intracellular Environment (Inside the Cell)

Think of it as a highly organized chemical factory where metabolism and life-sustaining reactions happen. Extracellular Environment (Outside the Cell)

Interaction Between Inside and Outside The plasma membrane controls what goes in and out, Transport proteins help move ions, glucose, and other substances and Receptors on the membrane detect signals (e.g., hormones) from the extracellular environment |

front 2 Explain the processes of diffusion and osmosis and the role they play in membrane transport. | back 2 Diffusion is the movement of molecules from an area of high concentration to low concentration until they are evenly spread out. No energy is required (it’s passive). Occurs with gases, small molecules, and some lipids. Ex: Oxygen moves from the lungs (high O₂) into the blood (low O₂) by diffusion. Osmosis is the diffusion of water across a selectively permeable membrane.

Ex: If a cell is in salty water, water moves out of the cell, causing it to shrink. Role in Membrane Transport: Both diffusion and osmosis are forms of passive transport, meaning the cell does not use energy. |

front 3 What factors affect the rate of diffusion? | back 3 Concentration Gradient Greater difference = faster diffusion Temperature Higher temperature = faster diffusion (particles move more quickly) Molecule Size Smaller molecules diffuse faster than larger ones Membrane PermeabilityIf the membrane is more permeable, diffusion is easier and faster Surface Area of Membrane Larger surface area = faster diffusion Distance (Thickness of Membrane) Shorter distance = faster diffusion Charge (for ions)Opposite charges attract and influence movement; may require channels Solubility in LipidsLipid-soluble substances (like oxygen or CO₂) diffuse faster through membranes |

front 4 What is the difference between morality and molality? | back 4 Molarity is the number of moles of solute per liter of solution. Depends on volume, which can change with temperature. Ex: If you dissolve 1 mole of NaCl in enough water to make 1 liter of solution, the molarity is 1 M. Molality is the number of moles of solute per kilogram of solvent. Depends on mass, which does not change with temperature. Ex: If you dissolve 1 mole of NaCl in 1 kg of water, the molality is 1 m. |

front 5 What are two requirements for osmosis to occur? | back 5 1. A Selectively Permeable Membrane The membrane must allow water to pass through, but not solutes (like salt or sugar). This creates a barrier that lets only certain molecules (usually water) move across. 2. A Difference in Solute Concentration on Each Side of the Membrane There must be an unequal concentration of solutes (e.g., salt or sugar) on the two sides of the membrane. Water moves from the side with lower solute concentration (more water) to the side with higher solute concentration (less water) to try to balance the solute levels. |

front 6 What is tonicity and how is it relevant clinically? | back 6 Tonicity describes how a solution affects the movement of water across a cell membrane by osmosis. It depends on the concentration of non-penetrating solutes (like salt or glucose) outside the cell compared to inside. Tonicity determines whether a cell will shrink, swell, or stay the same when placed in a solution. Tonicity is critical in medicine, especially when giving patients IV fluids. Clinical Examples: Isotonic IV solution (e.g., 0.9% NaCl) Used to maintain hydration without changing cell size. Common in trauma, surgery, and general fluid replacement. Hypotonic IV solution (e.g., 0.45% NaCl) Used if cells are dehydrated (e.g., in diabetic ketoacidosis). Must be used carefully—can cause cells to swell or burst if overused. Hypertonic IV solution (e.g., 3% NaCl) Used to reduce brain swelling or draw fluid out of swollen cells. Can cause cell shrinkage and must be used under close monitoring. |

front 7 Explain the negative feedback loop responsible for regulating blood osmolality. | back 7 Blood osmolality refers to the concentration of solutes (like sodium, glucose, and urea) in the blood. If blood becomes too concentrated (high osmolality) or too dilute (low osmolality), the body uses a negative feedback loop to restore balance and maintain homeostasis. |

front 8 Describe the characteristics of carrier-mediated transport and explain differences between active and passive forms. | back 8 Carrier-mediated transport involves the movement of substances across a cell membrane with the help of carrier proteins embedded in the membrane. These proteins bind specific molecules, change shape, and move them across the membrane — either with or against the concentration gradient. |

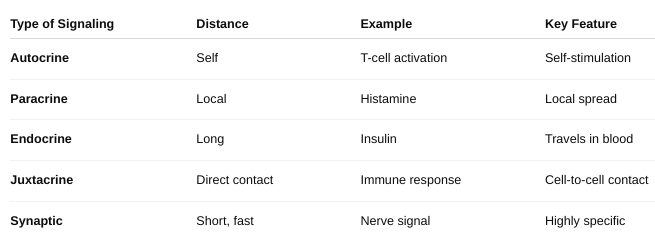

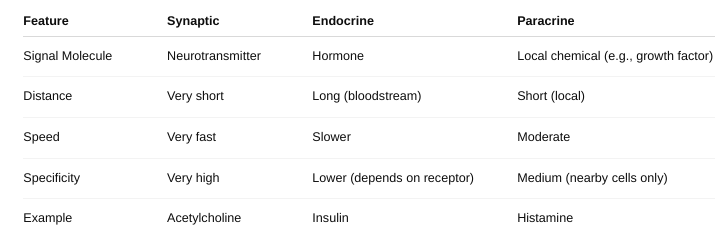

front 9 The different forms of cell signaling | back 9 Autocrine signaling: The cell sends signals to itself. Ex: Immune cells release signals to amplify their own response. Paracrine signaling: Signals are sent to nearby cells. Ex: Neurotransmitters between nerve cells. Endocrine signaling: Signals (usually hormones) travel through the bloodstream to reach distant target cells. Ex: Insulin from the pancreas acts on muscles and liver. Juxtacrine signaling (Direct contact): Cells communicate through physical contact via surface molecules. Ex: Immune cell recognition and embryonic development. Synaptic signaling: Specialized paracrine signaling used by neurons; neurotransmitters cross a synapse. |

front 10 The roles of second messengers and G-proteins | back 10 Second messengers are small molecules inside the cell that amplify and carry the signal from a receptor to the target molecules. They are created or released in response to a signal and help trigger a cellular response. Ex:

G-proteins (Guanine nucleotide-binding proteins) are molecular switches that help relay signals from receptors (like G protein-coupled receptors or GPCRs) to other proteins inside the cell. How G-proteins work:

|

front 11 Why are second messengers necessary for certain cell signaling? | back 11 Amplification of the Signal: One receptor activation can produce many second messengers, greatly increasing the strength of the signal Speed of Response: These small molecules diffuse quickly inside the cell, allowing for fast communication and rapid changes in cell activity. Signal Distribution: A single second messenger can influence multiple pathways or activate various target proteins. Regulation and Control: Second messengers allow for fine-tuning of responses based on concentration and feedback mechanisms. Passing Through Membrane Barriers: Since many signaling molecules (like hormones) act at the membrane, second messengers are needed to carry the message into the cell where it can cause changes. |

front 12 Explain the concept of membrane potential | back 12 the difference in electrical charge (voltage) across a cell’s membrane. It’s like a tiny battery: The inside of the cell is more negative compared to the outside. This voltage difference is crucial for nerve impulses, muscle contractions, and cell signaling. |

front 13 What establishes a resting membrane potential? | back 13

This resting state is essential for cells to fire action potentials, respond to stimuli, and maintain homeostasis. |

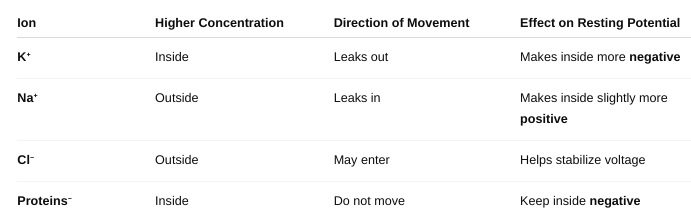

front 14 What ions are important for maintaining resting membrane potential? | back 14  |

front 15 How are these ions distributed across the membrane, and what

maintains this | back 15

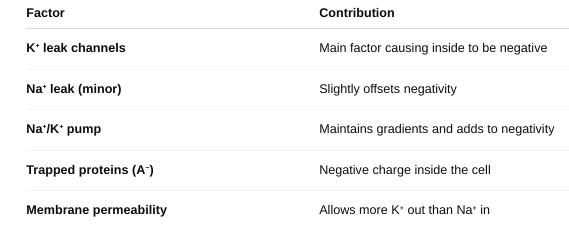

Maintained by:

Together, these factors create and maintain the resting membrane potential, which is critical for nerve and muscle cell function. |

front 16 What is the Nernst Equation and how is it used? | back 16 The Nernst equation is used to calculate the equilibrium potential (also called reversal potential) for a specific ion across a membrane. This is the voltage at which there is no net movement of that ion in or out of the cell because the electrical and chemical (concentration) forces are balanced. What Does It Tell Us?

|

front 17 Describe the process contributing to the resting membrane potential of the cell. | back 17  The resting membrane potential is the result of:

It sets the stage for action potentials, muscle contractions, and many cell functions. |

front 18 Describe the different types of cell signaling. | back 18  |

front 19 Distinguish among synaptic, endocrine, and paracrine regulation. | back 19  |

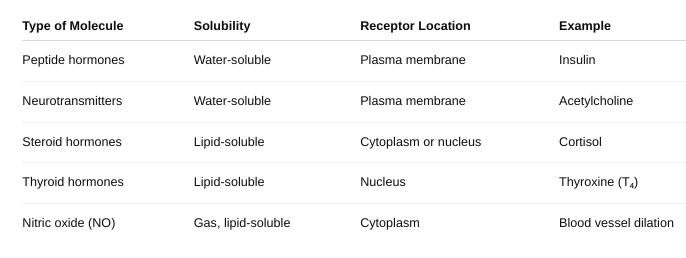

front 20 Identify the location of the receptor proteins for different regulatory molecules. | back 20  |

front 21 How do drugs work? | back 21 Drugs produce their effects by interacting with specific targets in the body—usually proteins such as receptors, enzymes, ion channels, or transporters. This interaction changes normal biological activity and causes a therapeutic or sometimes side effect.

Drugs work by mimicking, blocking, or modifying normal biological processes. Their effects depend on which target they interact with and how they interact (activate or inhibit). Understanding drug action helps in designing safer, more effective therapies. |

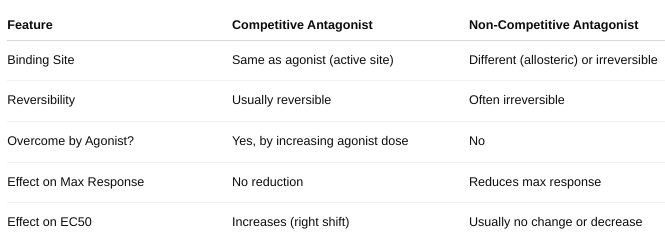

front 22 What is an antagonist? | back 22 An antagonist is a drug or molecule that binds to a receptor but does not activate it. Instead, it blocks or reduces the effect of an agonist (a molecule that normally activates the receptor). Result: The antagonist prevents the receptor from producing its usual response. |

front 23 Competitive vs non-competitive antagonist? | back 23  |

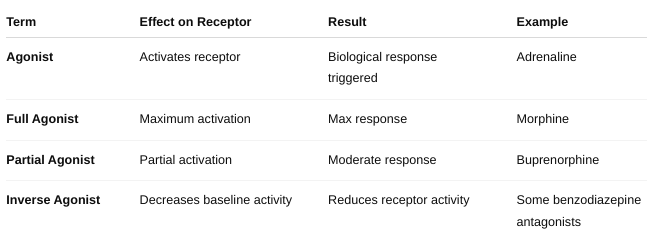

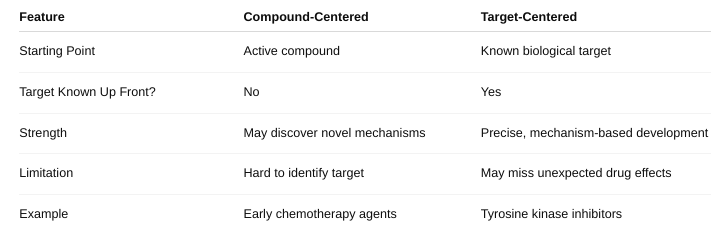

front 24 What is an agonist? | back 24  |

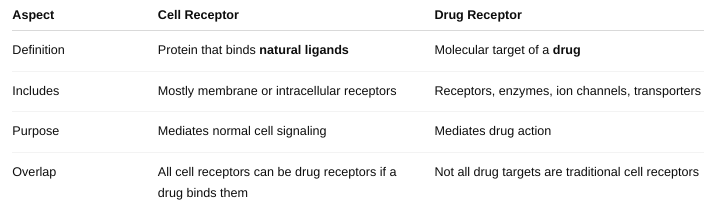

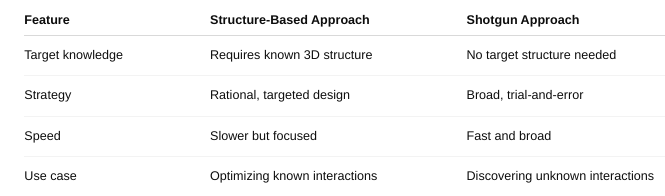

front 25 Define “drug receptor.” This may or may NOT be the same as a “cell

receptor.” | back 25  |

front 26 Can drugs produce “new cell functions?” Why or why not? | back 26 Generally, drugs do NOT create entirely new cell functions. Instead, they modify or influence existing cellular processes. Drugs Work by Modulating Existing Targets

Cells Have a Fixed Set of Functional Capabilities

No Creation of New Proteins or Structures by Drugs Directly While some drugs can indirectly affect gene expression (like steroids influencing protein synthesis), this is a modulation of existing functions, not creation of entirely new ones. |

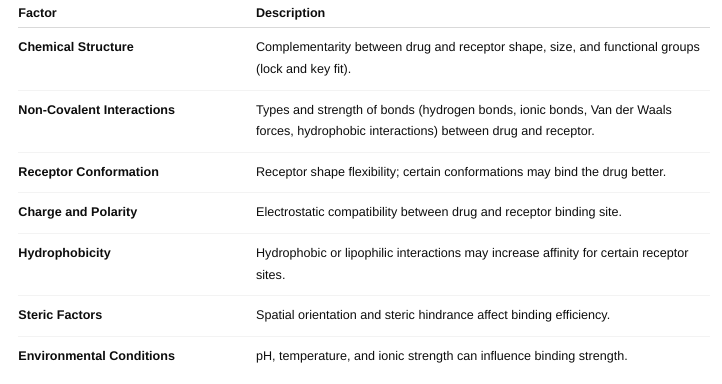

front 27 What are the factors affecting drug-receptor interactions? | back 27 Affinity: How strongly a drug binds to its receptor. Higher affinity means the drug binds more tightly and is effective at lower concentrations. Drug Concentration: More drug molecules increase the chance of receptor binding (up to receptor saturation). Receptor Density: The number of receptors available on/in the cell affects the overall response. Receptor Conformation (State): Receptors can have active or inactive shapes; drugs may bind preferentially to one state. Competition: Other molecules (agonists, antagonists) competing for the same receptor affect drug binding. Chemical Properties of the Drug: Size, shape, charge, hydrophobicity affect how well the drug fits and binds. Environmental Factors: pH, temperature, and ionic strength can influence binding affinity. |

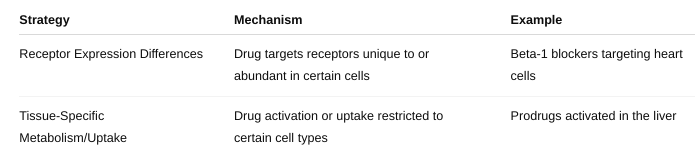

front 28 Drug-receptor selectivity? | back 28 A drug’s ability to preferentially bind to a specific receptor subtype or a limited group of receptors rather than many different types. Highly selective drugs tend to cause fewer side effects because they affect only certain pathways. Selectivity depends on:

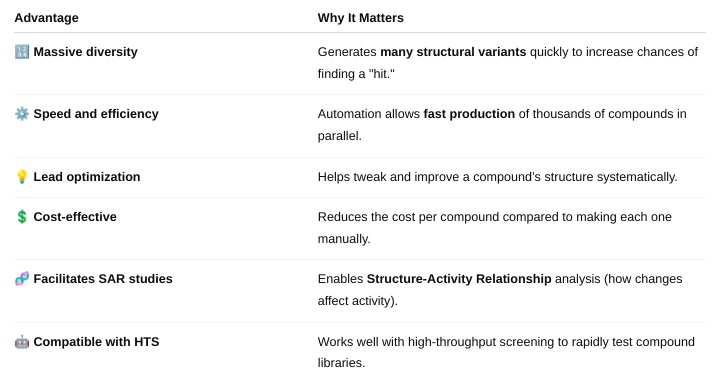

|

front 29 What is affinity? (Figure 1-1 and Table 1-1) | back 29 Affinity influences the potency of a drug — drugs with higher affinity generally require lower concentrations to elicit a response. It affects how well a drug can compete with others (like natural ligands or other drugs) for receptor binding. |

front 30 What factors define affinity? | back 30  |

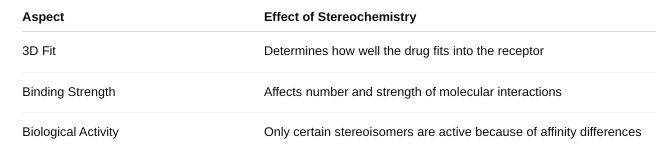

front 31 How does stereochemistry affect affinity? (Figure 1-2) | back 31  |

front 32 What is a racemic mixture? | back 32 a 50:50 mixture of two enantiomers of a chiral molecule. |

front 33 What are the TWO cell-type drug-specificity strategies? (Cell-type specificity) | back 33  |

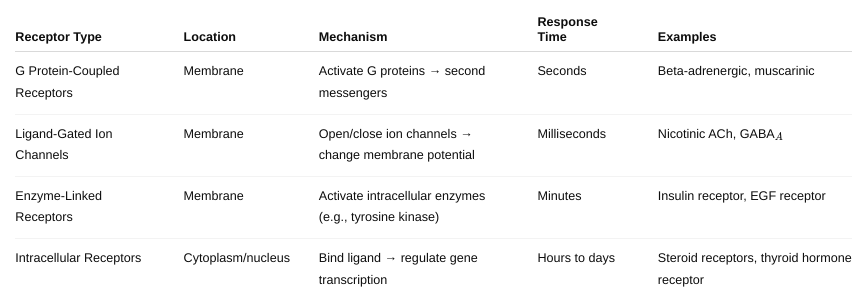

front 34 What are the major types of drug receptors and how do they work? Be

detailed. | back 34  |

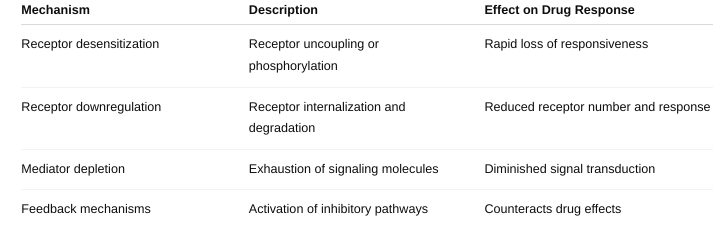

front 35 What are the different mechanisms of tachyphylaxis? (Figure

1-10; | back 35  Tachyphylaxis is a rapid decrease in the response to a drug after repeated or continuous administration |

front 36 Why is tachyphylaxis needed? | back 36 It’s a protective cellular mechanism to prevent overstimulation and damage from continuous exposure to certain drugs or signals. Prevents excessive cellular responses that could be harmful. Helps maintain homeostasis by adjusting receptor sensitivity based on ligand exposure. |

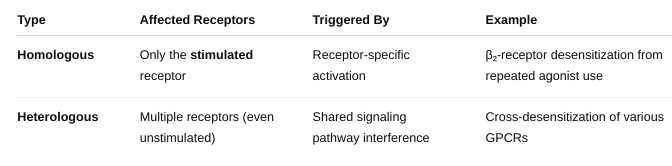

front 37 What is homologous vs heterologous? | back 37  |

front 38 Define: drug discovery | back 38 The process of identifying new candidate medications based on biological targets (like proteins, enzymes, or receptors) is involved in disease. It includes:

➡️ Think of it as the very beginning of the journey to making a new drug. |

front 39 Define hit | back 39 A "hit" is a chemical compound that shows promising activity against a drug target in an initial screen (often high-throughput screening). Characteristics:

➡️ A hit is like a rough gem — it shows promise but needs refinement. |

front 40 Define lead | back 40 A lead compound is a hit that has been optimized for better effectiveness, safety, stability, and selectivity. Characteristics:

➡️ A lead is a polished gem — a refined version of a hit that's ready for serious testing. |

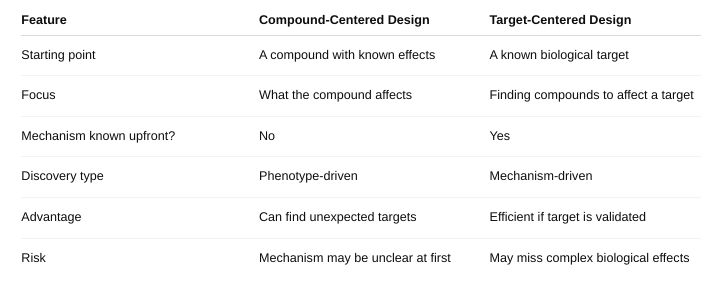

front 41 Define compound-centered and target-centered | back 41  |

front 42 Define structure-based approach and shotgun approach | back 42  |

front 43 What is compound-centered drug design versus target-centered drug design? | back 43  |

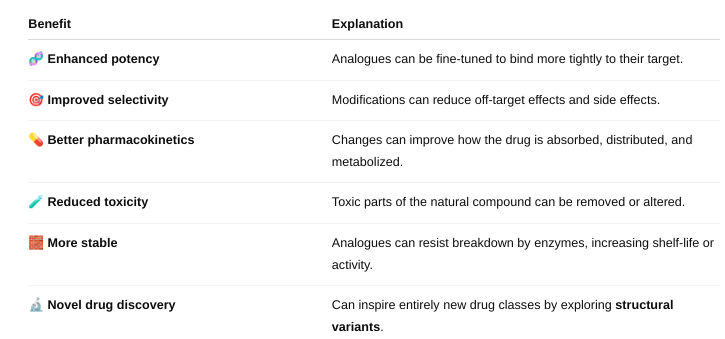

front 44 How are analogues of natural compounds used in drug design, and what

are the | back 44 modified versions of natural compounds (from plants, microbes, animals, etc.) How they’re used: Lead Optimization: A natural compound that shows some activity is used as a "lead compound." Chemists then modify parts of the molecule to improve: Potency (how strongly it works), Selectivity (how specifically it acts on the target), Safety (reduce side effects), Solubility or bioavailability (how well it's absorbed in the body) Overcoming Limitations: Natural compounds may degrade quickly, be hard to deliver, or have toxicity issues. Analogues are engineered to overcome these weaknesses. Creating Patentable Drugs: Natural compounds themselves may not be patentable. Chemically altered analogues can be patented, making them commercially viable. |

front 45 What are the potential benefits of analogues? | back 45  |

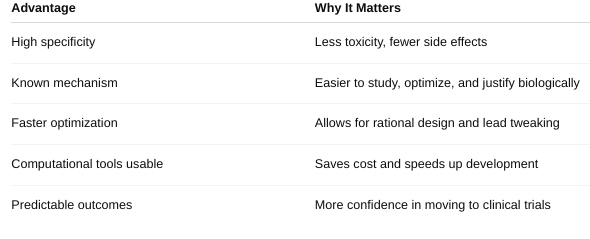

front 46 What are the advantages of target-centered drug design? | back 46  |

front 47 What is high-throughput screening? | back 47 a technology-driven process used in drug discovery to rapidly test thousands to millions of compounds for biological activity against a target (like a protein, enzyme, or cell). It’s like using a robotic assembly line to quickly find which chemicals might become drugs. How It Works:

|

front 48 How does high throughput screening facilitate drug discovery? | back 48 Speeds Up Discovery- Tests thousands of compounds in days, which would take years manually. Identifies Hits Early- Rapidly finds "hit compounds" that affect the target — a crucial first step in drug development. Works With Many Targets- Can be used on enzymes, receptors, ion channels, or even whole cells. Unbiased Discovery- Useful even when the mechanism is not fully understood — lets the biology "speak for itself." Data-Driven- Combines with machine learning and cheminformatics to spot patterns and optimize leads faster |

front 49 How does combinatorial chemistry allow researchers to generate a large number of chemical compounds, and what is/are the advantages? | back 49  Combinatorial chemistry is a method used to rapidly create large libraries of different chemical compounds by systematically combining sets of building blocks in all possible ways. |

front 50 What is structure-based drug design/rational drug design? | back 50 Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) — also called Rational Drug Design — is a method of designing drugs by using the 3D structure of a biological target (usually a protein or enzyme) to develop compounds that will bind to it in a specific and effective way. Think of it like designing a key to perfectly fit a lock — where the lock is the target (e.g., an enzyme's active site) and the key is the drug molecule |

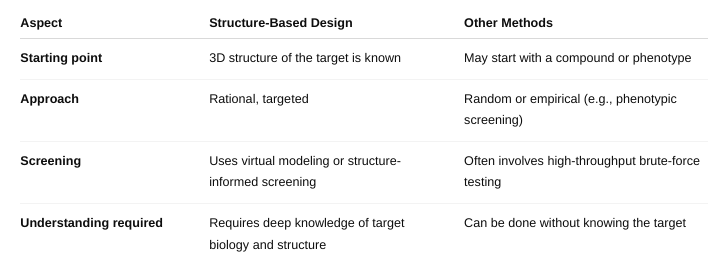

front 51 How is it different from other methods of drug design? | back 51  |

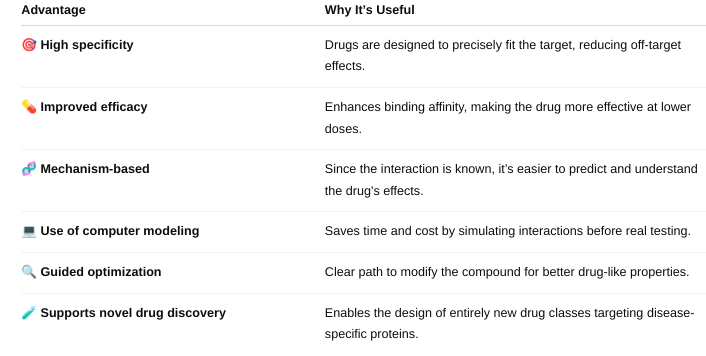

front 52 What are its advantages? | back 52  |

front 53 What is lead optimization? Where/when does it fit into the drug discovery timeline? | back 53 Lead optimization is a stage in the drug discovery process where scientists take a promising "lead compound" — a molecule that shows desired biological activity — and chemically modify it to improve its properties and make it a strong drug candidate. 1. Target Identification |

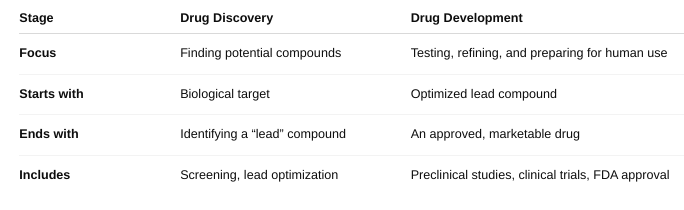

front 54 How does drug development relate to drug discovery? (Box 51-2) | back 54  |

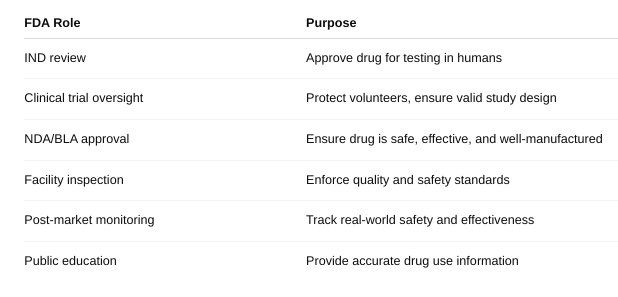

front 55 What role does the US Food and Drug Administration play in bringing drugs to market? | back 55  |

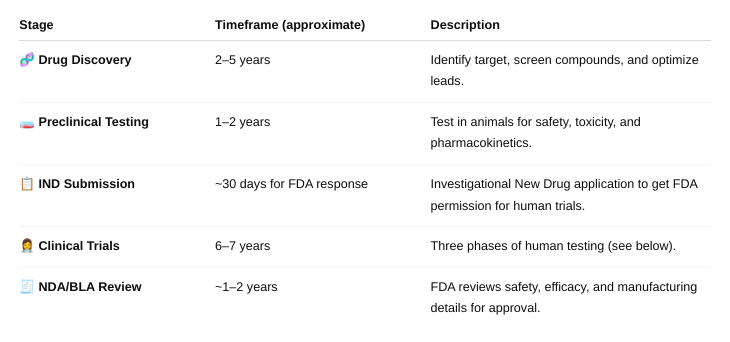

front 56 What is the estimated timeframe for drug development from drug discovery to approval of a new drug? | back 56  About 15 years |

front 57 What percentage of drugs entering clinical trials achieves approval? (Figure 52-1) | back 57 Only about 12% of drugs that enter clinical trials (human testing) are eventually approved by the FDA. |

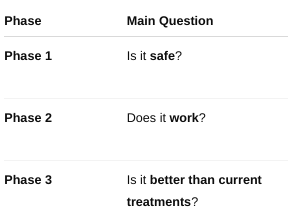

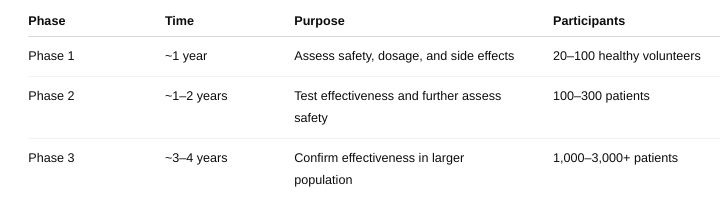

front 58 What are the three phases of a clinical trial? | back 58  |

front 59 What are the respective number of subjects involved, what is the length of each phase, and what is the purpose or focus of each phase? | back 59  |