Instructions for Side by Side Printing

- Print the notecards

- Fold each page in half along the solid vertical line

- Cut out the notecards by cutting along each horizontal dotted line

- Optional: Glue, tape or staple the ends of each notecard together

BMD 315 Module 1 Study Guide/ Learning Objectives

front 1 What is the structure of an atom? | back 1 An atom is the basic unit of matter and is made up of three main parts: Protons positively charged particles found in the nucleus. Neutrons neutral particles also in the nucleus. Electrons negatively charged particles that orbit the nucleus in electron shells or energy levels. |

front 2 What is the structure of an ion? | back 2 An ion is an atom or molecule that has gained or lost electrons, giving it a net charge: Cation: positive ion (lost electrons) Anion: negative ion (gained electrons) |

front 3 Ionic bond | back 3 Formed when electrons are transferred from one atom to another. Typically between a metal and a non-metal. Results in oppositely charged ions that attract each other. |

front 4 Covalent bond | back 4 Formed when atoms share electrons. Usually occurs between non-metal atoms. Can involve single, double, or triple electron pairs. |

front 5 Hydrogen bond | back 5 A weak attraction between a hydrogen atom (already covalently bonded to something electronegative like oxygen or nitrogen) and another electronegative atom. Important in stabilizing biological structures like DNA and proteins. |

front 6 Nonpolar covalent bonds | back 6 Electrons are shared equally between atoms. Happens when atoms have similar or identical electronegativities (ability to attract electrons). There is no partial charge on the atoms. Key Feature: Molecule has no poles (no distinct positive or negative ends). |

front 7 Polar covalent bonds | back 7 Electrons are shared unequally. One atom attracts electrons more strongly (is more electronegative), creating: a slightly negative (6-) end (where electrons hang out more) and a slightly positive (5*) end. Ex: In water, oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, so electrons spend more time near oxygen. Key Feature: Molecule has positive and negative poles, like a magnet. |

front 8 Why Are lons and Polar Molecules Soluble in Water? | back 8 Water is a polar molecule: It has a partial negative charge near oxygen and a partial positive charge near the hydrogen atoms. Polar molecules and ions are attracted to the opposite charges on water molecules. This attraction helps break them apart (dissolve them) in water. |

front 9 Acid | back 9 A substance that releases H + (hydrogen ions) in solution. Increases the concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution. |

front 10 Acidic/ Basic | back 10 A solution is acidic if it has more H+ ions than OH/ pH is less than 7. A solution is basic if it has more OH- ions than H+/ pH is greater than 7. |

front 11 Base | back 11 A substance that removes H+ ( hydrogen ions) from a solution or releases OH- (hydroxide ions). Decreases the concentration of hydrogen ions. |

front 12 What is pH and how does it relate to the concentration of H+? | back 12 pH is a scale that measures how acidic or basic a solution is. It is based on the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+). Formula: pH -log[H+] So, as [H+] increases, pH decreases (more acidic). As [H+] decreases, pH increases (more basic). |

front 13 What is a buffer? | back 13 a system that resists changes in pH when small amounts of acid or base are added. It usually consists of a weak acid and its conjugate base. In your body, a key buffer is the bicarbonate buffer system, important for maintaining blood pH around 7.35-7.45. |

front 14 The Bicarbonate buffer pair | back 14 In your body: Carbonic acid (H2CO3-)= weak acid Bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) = weak base They work together to keep your blood from getting too acidic or too basic. If the blood becomes too acidic: The bicarbonate ion (HCO3-) picks up the extra H+. Then carbonic acid breaks down into water and carbon dioxide, which is breathed out. If the blood becomes too basic (too much OH-): The carbonic acid gives up a hydrogen ion to neutralize the OH-. |

front 15 How Carbon bonds with other atoms and itself? (Via Covalent bonds, max = 4 bonds) | back 15 Other Carbons- Forms chains, rings, or branches. Can make single (-), double (=), or triple (=) bonds Hydrogen (H)- Forms simple C-H bonds Found in fuels like methane (CH4) Oxygen (O)- Can form: C-0 (single bond) or C=0 (double bond) Nitrogen (N)- Can form: C-N (single bond) or C=N (triple bond) |

front 16 Different types of Carbohydrates | back 16 Monosaccharides (simple sugars) One sugar unit, Quick energy source Examples: Glucose, Fructose, and Galactose Disaccharides (two sugar units) Ex: Sucrose = glucose + fructose, Lactose = glucose + galactose, and Maltose= glucose + glucose Polysaccharides (many sugar units) Long chains of sugars that are used for energy storage or structure Examples: Starch, Glycogen, and Cellulose |

front 17 Different types of lipids | back 17 Fats and Oils (Triglycerides) Made of 1 glycerol + 3 fatty acids Saturated Fats [Fats solid at room temp (animal fat)] Unsaturated Fats [Oils = Iiquid at room temp (olive oil)] Phospholipids Main part of cell membranes Have a water-loving head and a water-hating tail Example: Phospholipids in your cell walls Steroids Ring-shaped lipids that are used as hormones or cholesterol Examples: Cholesterol (in cell membranes) Testosterone and estrogen |

front 18 Dehydration synthesis (build up) of Carbohydrates and Lipids | back 18 In Monosaccharides (simple sugars like glucose) join to form disaccharides or polysaccharides. Example: Glucose + Glucose -> Maltose + Water What happens: An -OH (hydroxyl) group from one sugar and an H from another sugar are removed. They form H2O (water). The sugars bond via a glycosidic bond. In Triglycerides (fats): Made by joining 1 glycerol and 3 fatty acids. Example: Glycerol +3 Fatty Acids -> Triglyceride + 3 Water What happens: Each fatty acid attaches to glycerol by removing a water molecule. The bond formed is called an ester bond. |

front 19 Hydrolysis (break down) of Carbohydrates and Lipids | back 19 In Carbohydrates: Breaks polysaccharides into monosaccharides. Example: Maltose + Water -> Glucose + Glucose What happens: A water molecule is added. The glycosidic bond is broken. In Triglycerides: Breaks fats into glycerol + 3 fatty acids. Example: Triglyceride + 3 Water -> Glycerol + 3 Fatty Acids What happens: Water helps break the ester bonds. |

front 20 Describe the nature of Phospholipids | back 20 Found in cell membranes. Made of: 2 fatty acid tails (hydrophobic – "water-fearing"), 1 phosphate group head (hydrophilic – "water-loving") and 1 glycerol backbone Nature: Amphipathic: Has both hydrophobic and hydrophilic parts. In water, they form bilayers, which are the basis of cell membranes. The hydrophobic tails face inward, away from water, while hydrophilic heads face outward, toward water. |

front 21 Describe the nature of Prostaglandins | back 21 Derived from fatty acids Not part of membranes—these act more like hormone-like messengers. Have a five-membered carbon ring and two side chains. Hydrophobic but work in watery environments Nature: Act locally, not throughout the body (unlike hormones).

|

front 22 Description of amino acids | back 22 the building blocks of proteins. Each amino acid has the same basic structure: Amino group (—NH₂), Carboxyl group (—COOH), Hydrogen atom (—H), and R group (side chain) – varies between amino acids and determines their properties. All four parts are bonded to a central carbon (called the alpha carbon). There are 20 common amino acids, each with a unique R group. |

front 23 How peptide bonds are formed? | back 23 A peptide bond links amino acids together to form proteins or polypeptides. Amino acid 1's —COOH (carboxyl group) + Amino acid 2's —NH₂

(amino group) |

front 24 How are peptide bonds broken down? | back 24 To break a peptide bond, water is added (hydrolysis) The bond is broken, restoring the original —COOH (carboxyl group) and —NH₂ groups (amino group) on the separate amino acids. |

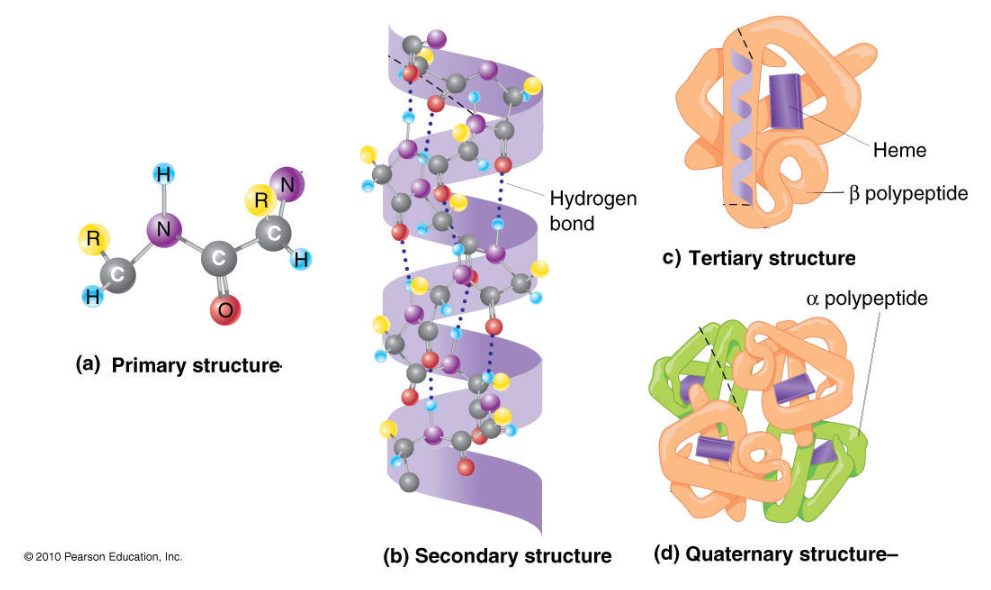

front 25  The Four Orders of protein structures | back 25 Primary Structure The sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. It is held by Peptide bonds.

Secondary Structure Local folding of the chain into α-helices (coils) and β-pleated sheets (folds) . It is held by Hydrogen bonds between nearby backbone atoms.

Tertiary Structure The overall 3D shape of a single polypeptide. It is held by: Hydrogen bonds, Ionic bonds, Disulfide bridges, Hydrophobic interactions

Quaternary Structure

|

front 26 The different functions of proteins | back 26 Enzymes: Speed up chemical reactions. Ex: Amylase, DNA polymerase Transport: Carry substances across membranes or through blood. Ex: Hemoglobin, ion channels Structural: Provide support and shape to cells and tissues. Ex: Collagen, keratin Defense: Fight infection. Ex: Antibodies (immunoglobulins) Signaling: Carry messages between cells. Ex: Insulin, growth hormone Movement: Help cells or muscles move. Ex: Actin, myosin Storage: Store ions or amino acids. Ex: Ferritin (iron storage) |

front 27 How Structure Gives Function Specificity? | back 27 A protein's shape = function. The 3D structure of a protein allows it to fit like a lock and key with its specific target (like a substrate for an enzyme). Even a small change in the amino acid sequence (primary structure) can change the folding, shape, and destroy or alter the function. Ex: Enzyme active sites are shaped to bind only to specific molecules.

|

front 28 Describe the structure of a nucleotide | back 28 the basic building block of nucleic acids

(DNA and RNA). Phosphate group (PO₄³⁻) Sugar

Nitrogenous base

|

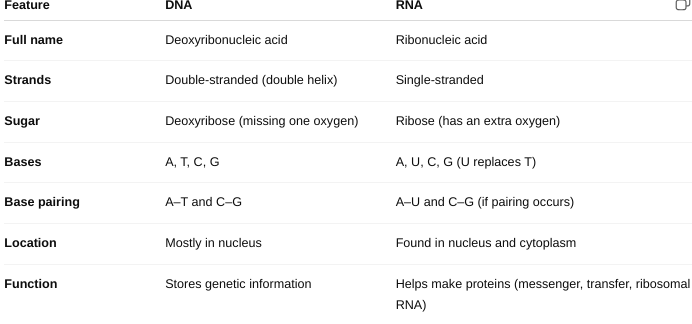

front 29 The structural differences between DNA and RNA | back 29  |

front 30 What is the law of complementary base pairing? | back 30 states that in DNA, specific nitrogenous bases always pair with each other in a consistent way: Adenine (A) always pairs with Thymine (T) Cytosine (C) always pairs with Guanine (G) |

front 31 How does the law of complementary base pairing work between DNA strands? | back 31 DNA is made of two strands twisted into a double helix. These strands are held together by hydrogen bonds between the bases. A–T form 2 hydrogen bonds C–G form 3 hydrogen bonds Because of this rule: One strand determines the sequence of the other. It ensures accurate DNA replication—each strand serves as a template, maintains genetic stability over generations and prevents random or mismatched pairing, which would lead to mutations. |

front 32 Describe the structure of the plasma (cell) membrane | back 32 Function: Acts as a selective barrier, controlling what enters and leaves the cell. Structure: Made of a phospholipid bilayer Hydrophilic heads (face water) and Hydrophobic tails (face inward) Contains: Proteins (for transport, signaling, and structure), Cholesterol (adds stability and fluidity), and Carbohydrates (for cell recognition and communication) Key Feature:

|

front 33 Describe the structure of cilia | back 33 Function: Move fluids across the surface of cells (e.g., mucus in the respiratory tract) and can also play sensory roles. Structure: Short, hair-like projections, made of microtubules in a 9 + 2 arrangement: 9 pairs of microtubules around the outside and 2 single microtubules in the center

|

front 34 Describe the structure of flagella | back 34 Function: Move the entire cell (like sperm cells swimming) Structure: Long, tail-like projection, the same 9 + 2 microtubule structure as cilia and also anchored by a basal body |

front 35 Amoeboid Movement | back 35 A type of movement used by cells like amoebas and white blood cells. The cell forms pseudopods (“false feet”) by extending part of its cytoplasm. The cytoplasm flows into the pseudopod, pulling the cell forward. This is driven by the cytoskeleton (especially actin filaments). Function: Allows crawling movement and helps cells hunt or move through tissues. |

front 36 Phagocytosis ("Cell Eating") | back 36 A form of endocytosis where the cell engulfs large particles (e.g., bacteria, dead cells). The membrane wraps around the target and forms a vesicle called a phagosome. The phagosome then fuses with a lysosome, which digests the material. Function : Used by immune cells like macrophages to destroy invaders |

front 37 Pinocytosis ("Cell Drinking") | back 37 Another form of endocytosis where the cell takes in fluids and small molecules. The membrane pinches inward, forming a small vesicle of fluid. Function: Helps cells take in nutrients and maintain fluid balance. |

front 38 Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis | back 38 A selective form of endocytosis. Receptors on the cell surface bind to specific molecules (like cholesterol or hormones). Once bound, the membrane folds inward to form a vesicle. Function: Allows cells to take in specific substances in concentrated amounts. |

front 39 Exocytosis | back 39 Opposite of endocytosis. A vesicle inside the cell fuses with the plasma membrane, releasing its contents outside the cell. Used to remove waste or release hormones, enzymes, or neurotransmitters. Function: Secretes important substances and maintains membrane balance. |

front 40 The structure and functions of cytoskeleton | back 40 Structure: A network of protein fibers inside the cell. Made of: Microfilaments (actin): thin, flexible fibers Intermediate filaments: medium-sized, rope-like Microtubules: thick, hollow tubes (made of tubulin) Functions: Supports cell shape, helps with movement (inside and outside the cell), guides organelle positioning and transport, and forms cilia and flagella |

front 41 The structure and functions of lysosomes | back 41 Structure: Small, membrane-bound vesicles filled with digestive enzymes Functions: Break down worn-out cell parts, bacteria, and macromolecules, known as the cell’s "recycling center" and important for immune responses and cell cleanup |

front 42 The structure and functions of peroxisomes | back 42 Structure: Small, membrane-bound organelles (like lysosomes) and contain enzymes (like catalase) that break down toxins Functions: Break down fatty acids, detoxify harmful substances (e.g., hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen), and protect cells from oxidative damage |

front 43 The structure and functions of mitochondria | back 43 Structure: Bean-shaped organelles with double membranes Outer membrane: smooth Inner membrane: folded into cristae for surface area Inside: matrix (fluid-filled space) Functions: Produce ATP (cell’s energy) through cellular respiration, known as the “powerhouse” of the cell and also involved in apoptosis (controlled cell death) |

front 44 The structure and functions of ribosomes | back 44 Structure: Small, round structures made of RNA and proteins

Functions: Make proteins by linking amino acids together using instructions from mRNA

|

front 45 The structures and functions of the endoplasmic reticulum | back 45 Rough ER (RER) Structure: A network of flattened membranes with ribosomes attached to the surface. Function: Makes proteins (with the help of ribosomes), modifies proteins (e.g., adds sugar chains), and sends proteins to the Golgi in transport vesicles Smooth ER (SER) Structure: Similar to rough ER, but no ribosomes and more tubular in shape Function: Makes lipids (fats, oils, steroid hormones), detoxifies drugs and alcohol, and stores calcium in muscle cells |

front 46 The structure and functions of the Golgi Complex (Golgi Apparatus) | back 46 Structure: A stack of flattened, membrane-bound sacs (like pancakes) Function: Receives proteins and lipids from the ER, modifies them (e.g., adds sugar or phosphate groups), sorts and packages them into vesicles, and send them to their final destinations (inside or outside the cell) |

front 47 How do the ER and Golgi Apparatus work together? | back 47 Proteins/lipids are made in the ER

Transport vesicles carry them from the ER to the Golgi

|

front 48 The structure of the nucleus | back 48 Function: Controls the cell's activities and stores genetic information (DNA). Structure: Nuclear envelope: Double membrane that surrounds the nucleus; has pores to let things in/out. Nucleoplasm: Jelly-like fluid inside the nucleus. Nucleolus: Dense area that makes ribosomes. Chromatin: DNA + proteins |

front 49 The structure of chromatin | back 49 Chromatin = DNA + histone proteins

|

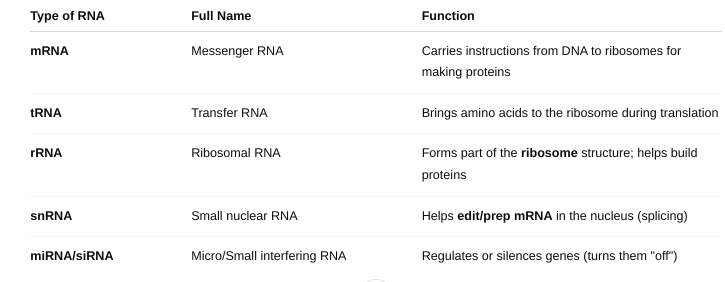

front 50 The types of RNA | back 50  |

front 51 How DNA directs the synthesis of RNA in genetic transcription? | back 51

Transcription is the process by which a gene

on DNA is copied into RNA. Steps of Transcription Initiation: The enzyme RNA polymerase binds to a promoter (a specific DNA sequence at the start of a gene). This signals where transcription should start. Elongation: RNA polymerase unzips the DNA strand (just one section).

Termination: When RNA polymerase reaches a termination sequence, it stops. The new RNA strand (usually mRNA) detaches.The DNA zips back up. |

front 52 The Key Players in Transcription | back 52

|

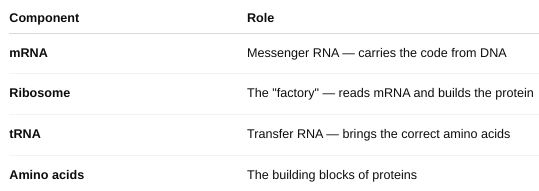

front 53 How RNA directs the synthesis of proteins in genetic translation? | back 53 Translation is the process where the genetic code in mRNA is used to build a protein (a chain of amino acids). It’s the second step of gene expression: mRNA is read in groups of 3 bases called codons. Each codon codes for one amino acid. Steps of Translation Initiation: The ribosome attaches to the start codon (AUG) on the mRNA. The first tRNA brings the amino acid methionine. Elongation: The ribosome reads the next codon on the mRNA. A tRNA with the matching anticodon brings the correct amino acid. The ribosome links amino acids together with peptide bonds to form a chain. Termination: When the ribosome reaches a stop codon (e.g., UAA, UAG, UGA), translation stops. The protein chain is released and folded into its final shape. |

front 54 The Key Players in Translation | back 54  |

front 55 How proteins are modified after translation? | back 55 After a protein is made through translation, it often needs to be modified to become functional. These changes are called post-translational modifications. Folding: Protein folds into its correct 3D shape (often with help from chaperone proteins) Cleavage: A piece of the protein is cut off to activate it Phosphorylation: A phosphate group is added (can turn protein on/off) Glycosylation: Sugar chains are added (important for cell recognition and signaling) Lipidation: Lipid added for membrane anchoring Disulfide bonds: Help stabilize protein structure These modifications happen in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, or cytoplasm depending on the protein’s role. |

front 56 How ubiquitin and the proteasome are involved in breaking down proteins? | back 56 Sometimes proteins are: Misfolded, Damaged and No longer needed They must be removed to keep the cell healthy. Ubiquitin: A small protein that acts like a "tag". It is attached to proteins that need to be destroyed. The process is called ubiquitination. Multiple ubiquitin tags = “this protein must go!” Proteasome: A large protein complex (like a molecular paper shredder). It recognizes and destroys proteins that are tagged with ubiquitin. It breaks them into small peptides or amino acids that the cell can reuse. |

front 57 Explain the semiconservative replication of DNA in DNA synthesis. | back 57 Semiconservative replication means that when DNA is copied, each new DNA molecule contains one original (parent) strand and one new strand. Steps of DNA Synthesis (Replication) Unwinding the DNA The enzyme helicase unzips the double helix by breaking the hydrogen bonds between base pairs. This forms a replication fork (Y-shaped opening). Priming Primase lays down a short RNA primer to start the new strand. Building New Strands DNA polymerase adds new nucleotides to the exposed bases using base pairing rules: A pairs with T, C pairs with G, One strand (the leading strand) is built continuously. The other strand (the lagging strand) is built in pieces called Okazaki fragments and later joined by DNA ligase. Result Two identical DNA molecules are formed.

|

front 58 The Cell Cycle | back 58 the series of stages a cell goes through to grow and divide into two identical daughter cells. Phases of the Cell Cycle Interphase – the longest phase (cell prepares to divide)

Mitotic Phase (M phase) – actual cell division

G0 phase – some cells exit the cycle permanently (e.g., nerve cells) |

front 59 Factors that affect the cell cycle | back 59

If any errors or damage are detected, the cell can pause the cycle or self-destruct. |

front 60 The significance of apoptosis | back 60 A controlled, safe way for cells to self-destruct when they’re old, damaged, or no longer needed. Protects the body by removing damaged or cancer-prone cells, Shapes the body during development (e.g., removing webbing between fingers) and Maintains balance between cell growth and death Failure in apoptosis can lead to: Cancer (if damaged cells survive and divide), Autoimmune diseases (if immune cells that should die survive), and Degenerative diseases (if too many cells die) |

front 61 The Phases of Mitosis | back 61

Purpose: To create two identical diploid

cells (same number of chromosomes as the original

cell). Prophase: Chromosomes condense and become visible, Spindle fibers form, and Nuclear envelope breaks down Metaphase: Chromosomes line up in the middle of the cell Anaphase: Sister chromatids are pulled apart to opposite sides Telophase: Chromosomes uncoil, and Nuclear envelopes reform around each set Cytokinesis (not part of mitosis but follows it)- Cytoplasm divides, forming two identical daughter cells |

front 62 The Phases of Meiosis | back 62

Purpose: To create four genetically unique

haploid cells (with half the chromosome number). Meiosis I – Separates homologous chromosomes Prophase I: Chromosomes pair up (synapsis), Crossing over occurs (genes are exchanged) Metaphase I: Paired chromosomes line up in the middle Anaphase I: Homologous chromosomes separate (not sister chromatids) Telophase I & Cytokinesis: Two haploid cells form (each with half the chromosomes) Meiosis II – Separates sister chromatids (like mitosis) Prophase II: New spindle fibers form in each haploid cell Metaphase II: Chromosomes line up in the center Anaphase II: Sister chromatids are pulled apart Telophase II & Cytokinesis: Four unique haploid cells are formed |

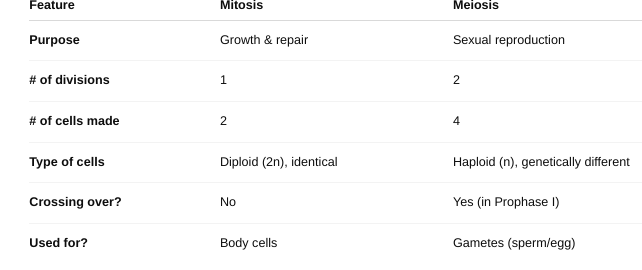

front 63 Meiosis vs. Mitosis | back 63  |